Aloko Udapadi: The Making of an Epic

The portrayal of Sri Lankan history by biographing a Sinhala king has become a staple of the local film industry going all the way back to 1974’s The God King, directed by Dr. Lester James Peries. But when Chathra Weeraman sat down to figure out how to cinematise an iconic tale of Sri Lanka’s history, he knew he had to disrupt the industry norms so as not to end up making another ‘historical film’.

Aloko Udapadi (Light Arose) marks the arrival of Chathra, and his Co-director Baratha Gihan Hettiarachchi, as fresh blood to an industry in disarray. The late Dr. D.B. Nihalsinghe, who was the founding CEO of the National Film Corporation, detailed the struggle of the local film industry to become a ‘true national cinema’ since 1950 in his book Public Enterprise in Film Development: Success and Failure in Sri Lanka. Film directors, producers and artists clash with the film governing body to bring practical solutions for issues such as film distribution, exhibition, production, finance and quality control. Meanwhile, poor theatre experiences are keeping local moviegoers away from cinema halls, many of which fail to meet basic standards.

Two decisive factors worried Chathra and his team. Firstly, Aloko Udapadi was their debut film. Secondly, the script was based on a series of occurrences with significant historical value—an epic film about the unswerving human effort to preserve a unique spiritual heritage. Chathra knew his work was cut out for him from the moment he was handed the ‘one-liner’—the bare-bones script—by his father Saman Weeraman, a well-known director and producer in the local film industry. Chathra took the challenge, but there were many times when he questioned himself about this decision.

However, when the trailer for Aloko Udapadi was released in 2015, Sri Lankan moviegoers were in for a pleasant surprise. The 3-minute trailer blazed a new era for Sri Lankan cinema through its novel approach to the epic genre, with meticulous production detailing and realistic visual effects. The trailer spread on social media platforms like wildfire, marking the arrival of a talented filmmaker.

Aloko Udapadi: A Synopsis

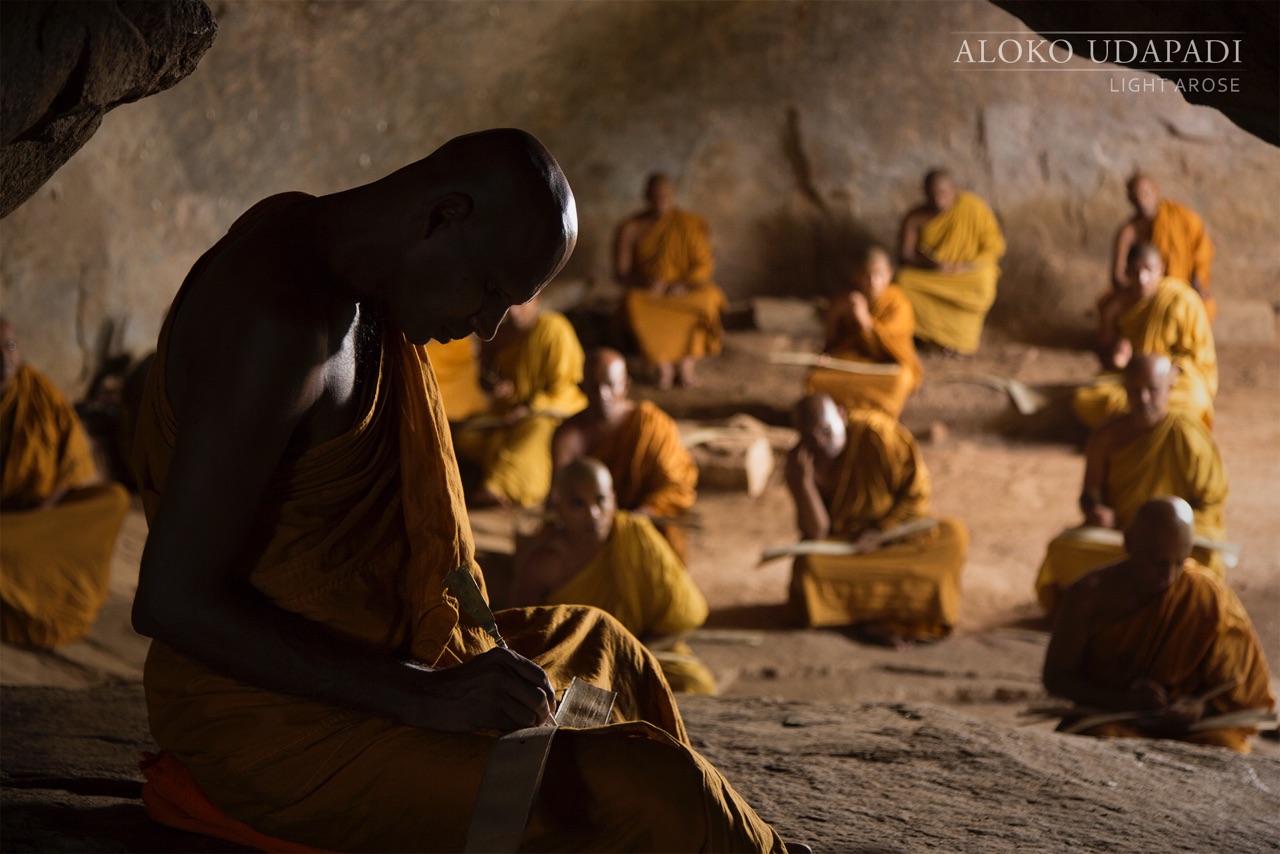

Aloko Udapadi narrates the story of Sri Lankan Buddhist monks, who recorded the teachings of the Lord Buddha in writing, 2100 years ago. Until that moment, the teachings of the Buddha had been brought down by oral tradition by dedicated Buddhist monks, spanning thirty eight teacher-student generations.

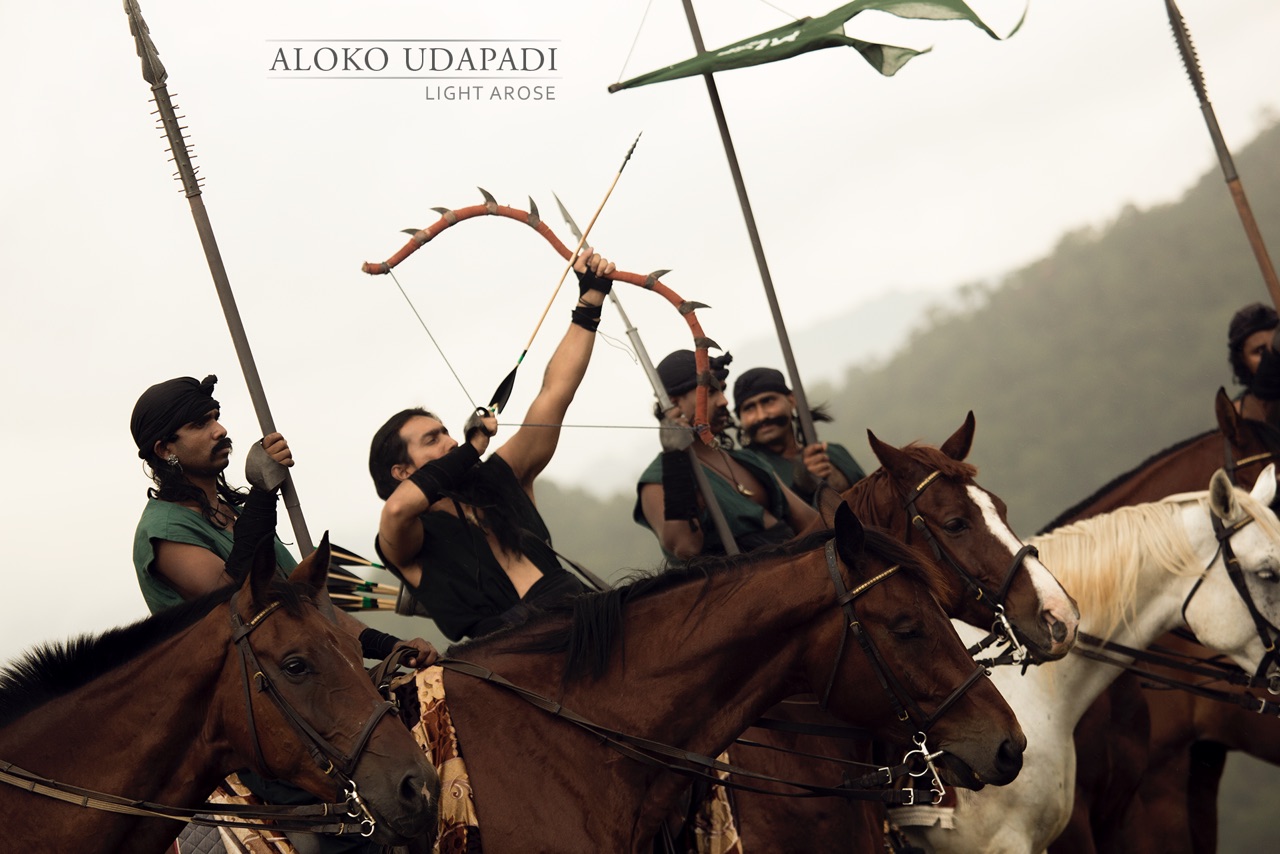

King Walagamba’s reign comes to a halt when seven Chola leaders invade Sri Lanka from across the seas. Worsening the situation, an internal rebel—Brahmin Theeya—rises against the king and demands the throne. Seeing Brahmin Theeya joining the invaders to topple the kingdom, the king flees, with the intention of returning in full force later on.

Enemies learn that the exiled king is being protected and supported by the Sangha, the Buddhist monastic community. They torture and massacre the innocent rural folk as well as the members of the Sangha in order to find details of the king’s hiding place. This leaves no option for the monks other than escaping to the forest to evade torture. Unfortunately that doesn’t stop them from being killed, as invaders continue their bloodbath. Meanwhile, Sri Lanka is overwhelmingly affected by a prolonged famine which continues for 12 years.

Under dire conditions, without any kind of food, the monks continue their duty to instruct the younger monks to learn the Word of the Buddha, sometimes teaching them with their dying breath. Deciding that hiding is useless, the king plans a strategy to rescue the country and the Buddhist religion, with the assistance of his supporters.

Driven by their own greed, the invading leaders start killing each other for the throne. While all this is going on, the king, with the support of locals, attacks the enemy hordes and recaptures the island. In a surprising miracle, nature brings the long-awaited rains, ending the 12-year famine.

To make the teachings of Lord Buddha more resilient to worldly conditions, members of the Maha Sangha decide that they should hold a council to commit them to writing, to prevent their decay. The Sangha assembles under royal patronage to fulfill this unprecedented spiritual task of writing down the Tipitaka.

The Production Process

From storyboards to visual effects to production designing, Aloko Udapadi marks a pioneering shift in the Sri Lankan film industry. The rigorous pre-production process continued for eight months, in contrast to the shooting of the film, which took only 62 days.

Hunting for Locations

The team had to travel to the northern part of the country to look for film locations. This ‘trekking of locations’, as Chathra calls it, started way before the pre-production stage.

“The locations had to be perfect in order to portray each and every scene of the film. The lush green, local settlements, arrival of Cholian invaders, fleeing of King Walagamba, battlegrounds and the famine which went on for 12 years: the locations had to be perfectly aligned with those scenes. We travelled for months like a set of invaders, seeking the perfect spots for filming,” says Chathra.

The film was shot in the driest parts of Anuradhapura and Kalpitiya, as well as in Teldeniya, a town in the Central Province. Chathra and company had to make sure that the chosen locations would not hinder the visual effects, colour corrections and colour grading, which were planned for the film’s post-production.

Pre-Production Starts

Being that this was a large-scale, epic film production, everyone in the crew understood that they had to work very hard. Throughout the eight months of post-production, Chathra had to manage a steady workflow to keep up with time constraints, rally everyone to perform their best, and maintain the quality of pre-production elements.

“For Aloko Udapadi, there were a number of production design elements to look at: costumes, weapons, visual effects, set creations, makeup, etc. We worked around a tight budget, meaning that we had to get involved in the process of pre-planning. Like beads in a well-crafted necklace, every element had to be arranged flawlessly. Failure to do so would have cost us a loss of nearly Rs. 500,000 per day. It was crucial in every sense,” Chathra opines.

Introduction of Production Designing

For the first time in the history of Sri Lankan filmmaking, Chathra introduced a concept called ‘production designing’, in order to amalgamate every design aspect and establish a common ground. In Hollywood and Bollywood, the role of the production designer is highly important. Working directly with the director, cinematographer and producer, he or she must select the settings and thematic style to visually narrate the story.

Chathra teamed up with his co-director Baratha Hettiarachchi to form the production design unit: a unique, collective force to collaborate with the art, costume and makeup departments of the film.

“Production designing was a key element throughout the pre-production process,” says Chathra. “Before each scene, the production designing team would discuss with the art, costume and makeup departments and analyse how the design elements of each department would tag along and how well colour combinations would work. These frequent chats gave us an idea about the perfect visual representation for a particular scene, so that there were no clashes between the set, costumes and makeup. The common colour disconnections we see in many local films were filled with the help of production designing.”

Designing Character Concepts

Based on the script, development began by incorporating visual metaphors and elements. The sole purpose of this was to maintain a seamless continuity of scenes in the film.

“The intention was to not disrupt the flow of thought of the audience. It was based on one simple concept: the scene you are watching right now should always be meaningfully connected and has to be foreshadowed by previous scenes,” Chathra points out.

Inclusion of visual components was then followed by creating character profiles. For instance, a personality check based on historical references was done for King Walagamba. Based on the determined character elements, concept artists started transforming those characteristics to drawings using pencil sketches. The preliminary sketches were developed to get a clear idea of each character’s appearance. Later, all the sketches were digitized to decide on colour schemes for characters, and with the help of these digital illustrations, the production team began figuring out who to cast as the main characters.

The film comprises four different groups: the king and the countrymen, the Cholian invaders, the Brahmins, and the community of Maha Sangha. Concept artists were given feedback on their distinctive characteristics, based on historical references, and they developed sketches for the production design team.

Designing of Different Environments

Thousands of photographs were taken at selected film locations, when Chathra and the team went to search for locations at an early stage of the pre-production process. These photos were given to the concept design team in order to develop blueprints of different environments. The look and feel of these different environments were then designed: battle camps of the Cholas and Brahmins, hiding places of the monks and King Walagamba, famine-hit villages and so forth. The beauty of this is that conceptualisation of environments was not done in imaginary geographies. Design aspects were accurately figured out by discussing the unique design visuals of each environment.

A team of researchers well-versed in Sri Lankan history was hired at the designing stage. They played an advisory role for the designers, providing accurate historical insights for the concepts developed by referring to chronicles like the Mahavamsa. Their feedback helped the production design team to realistically fit all design elements into the correct timeline.

Thumbnail sketches were then drawn to ideate the storyline before proceeding into storyboards.

Storyboards

With a big stack of concept art and sketches beside them, the design team started on the process of storyboarding.

Interestingly, every scene of Aloko Udapadi had been put into a storyboard, making a final tally of more than 700 storyboards: another first in Sri Lankan film industry. A storyboard is a sketch of how to organize a story and a list of its contents. It helps the production team to define the parameters of a story within the available resources and time, and to organize and focus the story.

“Storyboards gave everyone in the team an idea of different camera angles, camera compositions, the mise-en-scène and staging of actors,” says Chathra. “The entire process provided a comprehensive idea on how different scenes were going to be shot. Looking back, creating over 700 storyboards was a massive effort. No other Sri Lankan film has used this concept to such an extent.”

At different panel meetings, these hand-drawn storyboards were shared with actors and the director of photography.

Visual Effects of Aloko Udapadi

Visual effects (VFX) play a great role throughout the film. Even though Aloko Udapadi is an epic film, it did not have an epic budget. According to Chathra, that was one of the reasons why visual effects came in handy for his film.

Chathra studied visual effects and animation at the Multimedia University, Malaysia, for five years. Having done many short films and documentaries, he knew a thing or two about how to convincingly narrate a historical incident to moviegoers through VFX.

1. Set Extensions

Digital set extensions were used to conjure palaces and battle camps in the film. The production team built only the lower parts of the structures. The rest of the building layers were digitally extended using visual effects. The actual structures were built to add a physical dimension so that interaction would be easier for the actors.

2. Matte Paintings

Originally used in photography, matte paintings have evolved from painted glass panels to entire 3D digital worlds. In early Hollywood films, directors used paintings to visually create environments that were impossible to film, but now paintings have been superseded by computer-generated images and 3D designs.

Aloko Udapadi uses several matte paintings throughout the film. To showcase the disastrous period of the 12-year famine, matte painting was used by the VFX team. Another scene where matte painting was used was to recreate the Ruwanweliseya, then known as the Mahastupa, in 89 BC. During that period, it was heavily damaged. The VFX team used many photo references, especially the images of the stupa when it was rediscovered in 1902, to digitally sketch the structure and its background.

3. Crowd Multiplications

Since the film cast only had 200 extras, the VFX team had to digitally multiply the extras in battle scenes using crowd multiplication techniques.

“You place a camera and keep it static,” Chathra explains. “You ask the crowd to go to Place A and record it. The same crowd would go to Place B and we shoot the scene. The same crowd is circulated around the same terrain. We take both plates and superimpose them together. That was the easiest way of doing a crowd multiplication. We also shot them against a green screen and manually placed them in different places. In some scenes, we included computer-generated crowd shots as well where the shot was filmed from a far away distance.”

4. Computer-Generated Images (CGI)

The whole scene of the Cholian Invaders arriving in ships was created using CGI. Ships had to be first modeled using animation software. The CGIs were then added to an actual background frame taken on the shores of Kalpitiya.

From the beginning of deciding on VFX elements, Chathra never wanted to challenge or even go near the quality of a Hollywood production. There was a solid reason.

“We did not want to be too ambitious. The idea of using VFX was to create an impact which did not require us to do massive work behind the scenes. It was all about choosing the perfect shot and producing believable visual effects for the audience. We did not want to get ourselves stuck in an unrealistic VFX trap and reflect technical errors through our visual effects by trying the impossible, or rather trying to imitate what Hollywood does.

“We could have easily designed the insides of the fleet of ships, or pan a camera around the ships using VFX. No, we just wanted to give a realistic glimpse of our hard work to the audience and make that shot much more pragmatic,” says Chathra.

Post-Production Issues

Though it was less stressful than pre-production, Chathra had to endure several technical difficulties during the post-production period, simply because many key technologies were not available in Sri Lanka.

One such incident was completing the colour grading process of the film. Sri Lanka has some of the finest and experienced colourists and gradists, but sadly, technologies that are deemed proper by international standards have yet to materialize.

Since the industry had no colour calibrators and standardised colour grading studios, Chathra had to take the film copy to India, where he did the whole colourization process in a studio called Filmlab in Mumbai.

“It is very disheartening to see that proper technologies to do colour corrections and grading are still not available in Sri Lanka, even though we have a number of experienced colourists in the industry. Usually in other countries, the projectors in grading systems get calibrated once a week. In Sri Lanka, we have no such standardization. If the grading is done wrong, it will be distracting for viewers, jeopardising the whole story-telling aspect of the film,” Chathra says.

The entire Foley process had to be done in India as well. Foley processing is the reproduction of everyday sound effects that are added to film in post-production, to enhance audio quality. Since sound was not directly recorded on the Aloko Udapadi set, Chathra had to manually generate all the sound effects. From the swishing of clothing and footsteps to sword clashes, the entire Foley process was integrated into the film at Four Frames Sound Company in Chennai.

Not Another ‘Historical’ Film

The audience expects something momentous from epic films. The aim with Aloko Udapadi was to prove that epic films could be done in Sri Lanka, Chathra states.

“Sri Lankan historical films lack that essential ‘epic’ factor. Local moviegoers are every day exposed to many multi-million dollar Hollywood epic films, which means that a local film with the label ‘epic’ cannot deceive them by any means. They know what to expect out of an epic. With Aloko Udapadi, we wanted to change the norm of historical films in Sri Lanka. That is why we pushed several boundaries of filmmaking through concepts like visual effects,” says Chathra.

Unlike other historical films in Sri Lanka, Aloko Udapadi does not biograph a certain person – most commonly, the king. Rather, it depicts him in a unique way.

“He [King Walagamba] just plays a supportive role, and the rest of the cast contributes to the focal point of the film: the story of the recording of the Buddha’s dispensation in written form,” says Chathra. “Even when we shot the scene where the king eliminates enemy forces and reclaims the throne, there was no emphasis on his victory. It was a very dull scene, depicting how the king was not entirely happy about his feat, though he saved the country.”